Stage summary

| Storyline |

Caecilius and his household are introduced as they go about their daily business. The dog tries to steal some food while the cook is asleep in the kitchen. |

|---|---|

| Main language features |

The order in which information is delivered in a Latin sentence: Word order in sentences with est. |

| Sentences patterns |

nom + est + predicate (n/adj) nom + est + adverbial prepositional phrase nom + adverbial prepositional phrase + v |

| Cultural context |

Introduction to Pompeii; Caecilius and Metella’s household; houses in Pompeii. |

| Enquiry question |

Who was Lucius Caecilius Iucundus and what claims can we make about him and his household? |

Sequence and approach

The Cambridge Latin Course is designed to allow teachers to weave language and culture teaching together, and so while Stages in Book 1 are always laid out with cultural material at the end (for ease of navigation), this does not mean that you should always cover the stories and language content first. You may find it appropriate sometimes to study the cultural material before the stories, or you may wish to interleave the cultural material between stories.

The Enquiries given as part of the cultural material can be answered using only the material in English, but it can be valuable to encourage students to draw upon knowledge and understanding gained from reading the Latin as well.

For Stage 1, the cultural material might be taken in two parts, starting with the sections on Caecilius and Metella. Students could be asked to read this after they have met members of the household in the model sentences. The material on Roman houses might be studied in a subsequent class, possibly after the story has been read. If an Enquiry activity is being used, it would be set after the study of all material is completed.

Introduction

While not fabulously rich, Caecilius and his family would have been well off, and their comfortable life not representative of most people in Pompeii and the wider Roman Empire. Historical sources and literature often centre on a privileged and powerful minority. What voices do students think might be marginalised or missing from our sources and why? E.g. enslaved people, the poor, women.

Ask the class to look at the picture on the front cover. Explain that this is a portrait of a real Roman, Caecilius. Encourage them to study the portrait and its features (hooked nose, wrinkled forehead, receding hair, expressive eyes, wart etc.) and perhaps speculate on the kind of person he might have been.

Find out what students know about Pompeii. Explain that in Book 1 they will be reading about the lives of Caecilius and the members of his household in Pompeii in AD 79.

Illustrations: front cover and opening page (p. 1)

A bronze portrait head found in the house of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, Pompeii. The marble shaft supporting the head had the following inscription: Genio L(uci) nostri Felix l(ibertus) – To the guardian spirit of our Lucius; Felix, a freedman, (set this up).

It was long considered to be a likeness of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, the businessman who occupied the house at the time of the eruption of Vesuvius. Most scholars, however, now believe that the head portrays an earlier member of his family, perhaps his father. Nevertheless, it is a clue to our Caecilius’ appearance, and the line drawings in this book aim to show a family likeness to this shrewd but pleasant face. The head portrayed here is a copy of the original. (We have also introduced a freedman, Felix, in the stories of Stage 6.)

Model Sentences (pp.2-5)

New language features

Two basic Latin sentence patterns:

- the descriptive statement with est e.g. Caecilius est pater

- the sentence with the verb of action at the end e.g. pater in tablīnō scrībit.

First reading

The line drawings are intended to give the students strong clues so that they can work out for themselves the meaning of the Latin sentences. It is very important to establish the sentence as the basic unit and not to attempt to break it down and analyse it word by word at this stage.

Note that on pp. 2 and 3 the same sentence pattern is used throughout. On p. 4 that initial pattern is then slightly extended and locates each character in a particular place in the house. Finally, p. 5 builds the sentence pattern further by presenting the character in the same place, and now doing something. The vocabulary is recycled and from the outset the students should be encouraged to read the full Latin sentences from left to right rather than picking out isolated words and trying to piece together meaning.

Guide the class through the initial exploration of the model sentences. Read aloud the first sentence or set of sentences in Latin; give students a few moments to make their own attempts to understand. Do not comment about the grammar in advance. Let the students discover the sense of the sentence for themselves, helped by both the narrative and the visual context which generally give strong clues. Most students will grasp the grammatical point of a set of model sentences by the first or second example.

pp. 1–3

Read all the sentences in Latin and invite suggestions from the class about their meaning. Reread and ask for a translation of each.

p. 4

Ask leading questions about the drawings to help the students identify the characters and locations, with the order of your questions reflecting the order of the information in the Latin sentence; e.g.:

Who is in picture 8?

Look at what he is doing. Where do you think he would do that?

Who can now translate the Latin sentence Caecilius est in tablīnō?

In looking at the pictures for clues, students are likely to ask questions and make observations about the rooms in which the characters are located. Accept these but keep comment brief so that attention is focused on the Latin sentences.

After exploring the sentences with the class, ask individuals to read a sentence in Latin and translate it. Handle prepositional phrases such as in ātriō as a single unit of vocabulary and encourage students to supply the definite or indefinite article in English as appropriate.

p. 5

This page points up the differing word order of sentences with est and those with other verbs. The formula “find the subject, find the verb” is not appropriate and, if used, will become increasingly problematic as the sentence structures develop throughout the Course.

Instead, as on pp. 2–4, encourage students to read the Latin left to right, so that from the outset they become used to receiving information in the order in which it flows in Latin.

Give students a few moments to look at each picture and the accompanying Latin sentences. Then ask questions in English, using the picture as a guide. The technique of asking questions in this situation requires much thought and care. Couch the questions in concrete terms.

For example:

fīlia in hortō legit.

Q. Who is in the picture?

A. The daughter.

Q. Good. Where is she?

A. In the garden.

Q. Good. Is she writing or walking or reading?

A. Reading.

Q. Excellent. So what does the whole sentence mean?

A. The daughter is in the garden reading.

Q. Very good. How else might we say that in English?

A. The daughter is reading in the garden.

Students may make comments or ask questions. If so, confirm correct observations and help the students to form their own conclusions about what they observe. Do not yourself initiate discussion about the language until they have read the story which follows and are ready for About the language (p. 7).

You may wish to draw students’ attention to the use (or lack thereof) of capital letters: they are used only for proper nouns.

Students may translate servus in cubiculō labōrat (and similar sentences) as the slave / enslaved man is in the bedroom working. Do not reject this version but encourage alternatives, and students will themselves arrive at the slave / enslaved man is working in the bedroom or the slave / enslaved man works in the bedroom.

After this, discuss the line drawings more fully and follow up with work on the cultural context material (pp. 8–17). Among the points to note in the line drawings are:

Pp. 2-3

- As mentioned in the cultural background material on p. 9, Caecilius’ familia would have included enslaved people, freedmen and freedwomen, and others he had social ties to, as well as his wife and children. Clarify for students that this is not an indication that enslaved people were “part of the family” in the modern sense. ‘familia’ indicates part of the household rather than a close familial relationship. Caecilius is not portrayed as a particularly cruel dominus, but he would have had the power of life and death over the enslaved people in his household; many others treated the enslaved members of their household with far more brutality.

- Caecilius’ slightly grubby toga: it would have been impossible to keep the toga pristine. Also note that the other figures are in coloured clothing: the Romans did not only wear white.

- Metella’s skin is far paler than other characters in the pictures. This would have been achieved using cosmetics. It is not known which women wore this very pale makeup, nor how often or how extensively over their exposed skin, but we have imagined Metella to favour a very pale look and a very fashionable, large Flavian hairstyle.

- Cerberus is named after the mythical guard dog of Hades.

Pp. 4-5

- The study opening onto the garden; writing with pen and ink on a papyrus scroll; lamp (front right) with container for scrolls behind.

- The atrium as seen from the study; front door at far end with shrine to larēs at left; aperture in roof to admit air, light, and water, with pool to collect rainwater below; little furniture. Note that while the room in the picture is quite empty (so that students do not get distracted from the task at hand), in reality it is the main room of the house and would have been bustling and busy; this is why Metella is there: she is at the heart of the house overseeing all that is going on.

- In the dining room, a small table, with couches for reclining at dinner.

- Courtyard garden with colonnade for shelter from sun, plants in tubs and beds, statues, and fountain to refresh the air.

- Bedroom with little furniture besides a couch, cupboard, and small table.

- Cooking pots on charcoal fires, fuel store underneath.

- Chained guard dog at front door; high curb; no front lawn. The door open, but guarded, to allow air to flow through into the house and enable passersby to view the wealth of the owner.

Many of these points tie into material in the cultural background section.

The red pigment seen all over Pompeii is called cinnabar and was imported from Spain. This material was poisonous (as it contained mercuric sulfide) and very expensive. Extensive use of it is a good indicator of great wealth. Some of the ‘red’ discovered by archaeologists on the walls of Pompeii was however not actually red lead and cinnabar, but rather yellow ochre which was turned red by the hot gases from the eruption of Vesuvius. Italy’s National Institute of Optics has suggested that the balance between red and yellow would have been almost 50:50, but other scholars are doubtful that it is possible to be sure about the proportion of red to yellow. The line drawings of Caecilius and Metella’s house use a substantial amount of Pompeian red, on the assumption that Caecilius would have been able to afford the expensive red pigment. Yellow also has a significant presence however, to remind readers that we should not exaggerate the dominance of Pompeian red on the walls of the city.

Consolidation

Students could reread the model sentences for homework. At the beginning of the next lesson, give the students a few minutes in pairs to review the model sentences and refresh their memories, and then ask individuals to read and translate a sentence.

In subsequent lessons, use single sentences as a quick oral drill, and then gradually modify them, e.g. Caecilius in tablīnō labōrat (instead of scrībit).

About the language (p.7)

New language feature

The different word order in Latin sentences according to whether the verb is est or not.

Discussion

The focus here is the sentence as a whole; avoid breaking it down into parts. Take paragraphs 1 and 2 together as the core of the note, and paragraph 3 on its own.

Encourage students to read Latin from left to right from the outset, and to become used to information flowing in a different order from English.

Consolidation

Ask the students to find similar examples in the model sentences or the story.

Illustration

A typical Roman stove and bronze cooking pots found in the House of the Vettii in Pompeii. The pots would have been placed on a brazier over a small fire. Firewood would be stored in the alcove underneath. This image might be referenced later in this Stage when discussing house layouts or during Stage 2 when looking at food and cooking.

Reviewing the language (p. 222)

There is no Practising the language section for Stage 1. If your students would benefit from consolidation of knowledge of the characters and language in this Stage then exercises can be found at the back of the book in the Reviewing the language section. If your students seem secure in their understanding you may not wish to use these.

Exercise 1. Practice in the structure of sentences with est.

Exercise 2. Completion of sentence with appropriate prepositional phrase.

All options may be possible for each sentence but encourage students to select options which make good sense (usually based on the stories or model sentences) and to avoid answers which, though structurally feasible, produce unlikely situations. This is also an opportunity to highlight to students the experiences of the different characters, for example women, enslaved people, children. Have them consider how we might depict these people and what actions and situations might be likely for them.

Writing out correctly a complete Latin sentence and its translation, however easy, reinforces students’ confidence and grasp of the language. In Stage 1, as students write answers in their notebooks for the first time, it may be useful for the teacher to model what is expected, by doing one or two sentences, or even all of exercise 1 together before assigning the rest of the work in class or as homework.

Cultural context material (pp. 8-17)

Students are introduced to the members of the household and the house in which they lived and worked.

Enquiry

Who was Lucius Caecilius Iucundus and what claims can we make about him and his household?

All cultural background sections have an enquiry provided to prompt historical investigation. You do not have to use all (or any!) of them. Stage 1’s enquiry is focused on building student knowledge of the household of Caecilius. It also acts as an introduction to the nature of evidence from Pompeii and begins to develop student skill in using archaeology to make historical claims.

All enquiries can be assessed as pieces of long-form written work, however there are alternative approaches. Examples of such will be given in each Stage commentary. For this enquiry, possible outcome tasks include:

It is advisable to introduce students to the enquiry and the outcome task before undertaking study of the cultural background section so that students are reading the material with the outcome in mind. The section ends with several bullet points to help students understand how the material they have studied links to the enquiry to help them in structuring their work.

- Character profiles. Students to create short character profiles for all named members of the familia met in Stage 1. For each they should note down what we can infer about their lives; you may wish to encourage students to make a distinction between what is known and what is fiction, and for the latter why the authors have made the choices they have. This task might be done very successfully alongside study of the model sentences. For those who wish, this task could be consolidated using games such as ’20 Questions’ or ‘Guess Who?’ or a student who is an ‘expert’ on a character being in the ‘hot seat’ and asked questions about their lives (this exercise should be managed carefully. It is not advisable for students to take the roles of enslaved characters).

-

Interviews. This may lead on from the activities above. Students might think up interview questions they would like to ask characters, and then write a transcript of the imagined interview. Students may wish to be creative and lay their work out like a glossy magazine or gossip website. This may naturally not be appropriate for exploration of the enslaved characters.

Gatsby benchmark 4: Linking curriculum learning to careers

[https://www.gatsby.org.uk/education/focus-areas/good-career-guidance] This Stage’s cultural material introduces students to the work of different people who study the ancient world and offers an opportunity for conversations about career pathways.

Thinking points

Not all Thinking points need to be studied. Select those most relevant to your and your class’s needs and interests.

1. What can we learn about Caecilius from these items? What can’t we learn from them?

The below are possible answers only. Students may come up with many other points:

- Front of the house with shops on each side that he probably owned: successful businessman, although we do not know what these shops sold, whether they were profitable, or even that he definitely owned them.

- Wooden tablets found in his house: these tells us about some, but not all, of his business dealings. They do not give us context such as what he was like as a businessman; was he fair? A cheat? A good negotiator? Trustworthy?

- Re-creation of tablet: Caecilius handled the sale of enslaved people.

- Strong box: this is an example of a Roman strong box, and we can assume that Caecilius may have had something similar, but this is not his and so its usefulness is limited.

- The bust of Caecilius: this may tell us what he looked like, however there is debate as to whether it is actually him or a relative. We also do not know how accurate the likeness is.

2. Caecilius lists human beings alongside cloth, timber and property as ‘items’ he trades; what Roman attitude towards enslaved people does this reflect?

For Caecilius and those like him, enslaved people were considered property and were treated like objects to be bought and sold. While we cannot know the attitudes of every Roman, there is little evidence in the sources of voices calling for the abolition of slavery in the Roman world. It appears to have been very much normalised and accepted. Students should be encouraged to think critically. For example, our sources are dominated by enslavers, not the enslaved; if we had more views of enslaved people, we would probably see far more resistance and outrage at the practice.

3. What claims can we make about the status of Roman women compared with Roman men based on a) Roman names b) Roman marriage customs?

Both of these customs demonstrate the patriarchal nature of Roman society:

a) Roman women’s names were traditionally derived from their fathers, showing that the Romans thought of Roman girls and women as defined by their relationship to men.

b) Roman girls’ marriages, especially in upper class families, were usually arranged by their fathers (or other male guardian). This shows men’s control over women and a lack of freedom for women.

Arranged marriages are still common practice in many societies today. It is important to distinguish between ‘arranged’ and ‘forced’ marriage. The latter is illegal in many countries including the UK (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/forced-marriage). This is an opportunity to raise awareness of forced marriage in modern society and the resources available to help those at risk, e.g.:

Childline: https://www.childline.org.uk/info-advice/bullying-abuse-safety/crime-law/forced-marriage/

Refuge: https://refuge.org.uk/i-need-help-now/how-we-can-help-you/gender-based-violence-services/

4. Think back to the sentences at the beginning of the Stage and the story you have read; what do you already know about Caecilius’ house?

This Thinking point is only of use if you are looking at the cultural background after studying the model sentences and the story. If you have not done so yet simply do not use it; this is not a sign of doing things in the wrong order. If they have read the sentences and story then students should be able to identify some of the rooms and areas of the house and also the Latin words for them. Explain to students that where certain words in Latin are difficult to translate into English (because there is no direct equivalent, or the Roman concept is very specific), it is sometimes appropriate to leave these in Latin. For example, Roman dining rooms have a very specific set up with their three couches, so while ‘dining room’ is fine, many people choose to use the word ‘triclinium’ even when writing in English.

5. Why do you think wealthy Romans might have encouraged passersby to peer into their houses?

To show off how beautiful and rich their houses were. Students might look at the pictures on page 12 to see how easy it is to look into the doorway of the houses (as the street passes right by them). Also of note is the positioning of the impluvium and its surrounding decoration right where people can see them from the street.

6. Women like Metella were responsible for keeping the household running smoothly. In the sentences at the beginning of this Stage, Metella is seen sitting in the atrium. Why do you think she might choose to sit here? What activities might she be doing?

Students will offer a variety of responses to these questions, but discussion should draw out the role of the atrium as the busy heart of the house, and women such as Metella as the head of domestic affairs. She is sitting in the atrium so that she can oversee everything happening in her household and so that she is easily accessible to anyone wanting to speak with her. She may also be there in case visitors arrive.

7. Make a note of what types of evidence generally did and did not survive the volcanic eruption which destroyed Pompeii. Why do you think this is the case?

The items which survived the eruption were generally made of non-perishable material such as stone or metal. This is due to both the destructive force of the eruption itself (wood, for example, burns when exposed to heat), but also the years spent buried before discovery in which it rotted away. You may wish to ask students to suggest what items in their own homes might survive for future historians to study, and what would not. What claims might historians make about their lives? How accurate might they be?

8. Where is the tablinum located in the house? What does this tell us about how it was used?

The tablinum is located between the atrium and the peristylium and a person could walk through it to get from one area of the house to the other. It is not closed off by doors or especially private; students may compare this to a modern idea of an office or study which is usually a quiet space for someone to work uninterrupted. The implication is that this is a reasonably public space for business or matters which are not especially confidential or clandestine. Like the atrium, this room is located at the heart of the house and someone sitting in it would have an excellent view of what is happening in the house and would be easily accessible to anyone wishing to speak with them. In fact, it would be difficult to move around the house without someone in the tablinum being able to see or interact with you.

9. What did the Romans use their gardens for? How is this similar or different from today?

While some Roman gardens were ornately planted and obviously intended as pleasurable leisure spaces, others were working plots of land ranging from household vegetable patches to small farms or vineyards. Whether students find this striking or unusual will depend very much on their own context and experience. In inner-city areas the idea of most homes having a garden at all may seem strange. Many homes today grow vegetables or fruits in small amounts, however you would be unlikely to find a small farm or vineyard in the average household. Students may wish to draw comparisons with allotments or urban farms. This discussion could be an excellent opportunity to highlight the diverse range of homes and spaces both in the ancient and modern world.

10. What do you think are the biggest differences between Caecilius’ house and a modern home?

Students will have individual and very personal responses to this question which will be heavily dependent on their own circumstances and experiences. The question deliberately does not ask students to compare Caecilius’ house to their own home, so that if students are uncomfortable discussing their own living situation, they can still engage with the question by considering houses and homes more generally. If it is felt that an open discussion of homes and home lives might not be appropriate, teachers might use a clip of a TV property show or a house listing on a property website to illustrate a modern house and ask students to make comparisons based on that.

Further suggestions for discussion

- How can we reconstruct Pompeian houses and gardens on the basis of archaeological findings?

- The position of women in Roman society compared to a) that in which the students live and b) other societies in the modern world where women’s rights and freedoms might be very different.

- The role and position of enslaved people in Roman households and the feelings this evokes in us as a modern audience. Points may include:

- A reminder that the individuals depicted are not servants (despite this being a common misconception due to the similarity of the word servus) but enslaved; teachers may wish to highlight the differences between the two conditions.

- Translation of servus as “slave” or “enslaved person” is accurate, and both are offered in the book’s vocabulary list at the back. The latter may be preferred as it emphasises that being enslaved is not a natural part of any human being’s make up, and is instead an act of violence against them. This point is explored in Thinking Point 2 in Stage 6.

- The relationship of Clemens and Grumio to Caecilius. This is not friendship or ‘employer-employee’. The idea of the ‘good master’ should be avoided. Enslaving another person cannot be done in a manner which is ‘good’. Even if an enslaved person is ‘treated well’ or not physically abused, the act of enslavement itself – one of ‘social death’ - is one which has been shown to create deep seated trauma and pain.

Further resources for thinking and teaching about slavery can be found in the guidance for Stage 6.

Further information

The figure of 10,000 for the total population of Pompeii can only be approximate. According to Beard (2008), current estimates vary from 6,400 to 30,000.

Caecilius

The basis of our knowledge about Caecilius is 153 wax tablets containing his business records, which were discovered in 1875 in a strongbox or arca, in his house. While often described as a ‘banker’ he was more accurately a coactor argentarius (receiver of silver): a middleman or financial agent in transactions such as auctions, money lending etc. The tablets indicate the range and diversity of Caecilius’ financial interests. They include records of a loan, sales of timber and land, the rent for a laundry and for land leased from the town council, and the auction of linen on behalf of an Egyptian merchant. His commission was 2 percent.

A wine amphora found in the shop at the right of the housefront reads: Caecilio Iucundo ab Sexsto Metello (To Caecilius Iucundus from Sextus Metellus). An election notice mentions Caecilius’ two sons: Ceium Secundum II virum Quintus et Sextus Caecili Iucundi rogant (Quintus Caecilius and Sextus Caecilius ask for Ceius Secundus as duovir). This inscription gives us Quintus as the praenōmen (personal name) of one son. For simplicity, Sextus does not feature in our stories (although he is briefly mentioned on page 11). The names attributed to the rest of the household are invented as is discussed in Stage 1’s cultural background material.

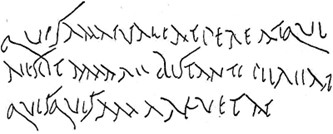

Visible from the street are the mosaic of the dog on p. 6 and the following graffito found in the tablinum:

He who loves should live; he who knows not how to love should die; and he who obstructs love should die twice.

The contents of the house (including several wall paintings) are currently in storage, either in Pompeii, or in the Archaeological Museum in Naples. Unfortunately, the famous marble lararium relief (images on p. 66 and 196 of student book), depicting scenes from the disastrous earthquake of AD 62 or 63, has been stolen and is accessible only in photographs.

Roman women

Conventions for the naming of Roman women changed over time. Originally – during the Republican period - a Roman woman had only one name, usually the feminine form of her father’s nōmen. For example, Gaius Julius Caesar’s daughter was called Julia. If there were more than one daughter, the names would be the same, distinguished by words such as “the elder,” “the younger,” “the first,” “the second,” “the third”: Julia Maior or Julia Prima, Julia Minor or Julia Secunda. In public women with the same name might be differentiated by the possessive form of their father's cognomen (Julia Caesaris, “Julia, the daughter of Caesar”) or that of their husband (Clodia Metelli, “Clodia, the wife of Metellus”).

By the late Republic conventions had begun to change. Elite Roman woman still used the feminine form of their father's nomen, but now added the feminine form of his cognomen, sometimes in the diminutive. For example, Augustus’ wife Livia, daughter of Marcus Livius Drusus, was Livia Drusilla. From the era of Augustus onwards, prominent women’s names often reflected dynastic and familial connections rather than following traditional conventions. Augustus' granddaughters, born to his daughter Julia and her husband Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, were called Julia and Agrippina rather than Vipsania. When Agrippina married Nero Claudius Germanicus, rather than naming their three daughters Claudia in reference to their father’s nomen, they were instead Agrippina, Drusilla, and Julia Livilla.

In terms of the stories, nothing is known about Caecilius’ wife and mother of his children; the character of Metella is entirely fictious, including her name. Lucia, Caecilius’ fictional daughter, is not—as she should be—called Caecilia (this was considered too confusing for students). We have imagined that she has perhaps two names, with one acquired (slightly unusually) from her father’s praenomen (his cognomen not being the most student friendly to use). Although a wider variety of naming conventions were becoming fashionable among the elites at this time, we admit that this is a piece of historical license on the part of the authors.

By the time of our stories the old forms of marriage had given way to a freer form in which the wife could end an unsuitable marriage by divorce while retaining possession of her own property, subject only to supervision by a guardian. Such guardianship was, apparently, treated merely as a formality and a woman had only to apply for a change in guardian if she found him unsuitable. After the time of Augustus (63 BC – AD 14), a woman could inherit property, although the law restricted the amount. Women found ingenious ways of circumventing this law: several were themselves full heirs and passed on their property to chosen heirs through their wills.

Most of our knowledge about the status of women refers to those in the upper-class. A Roman girl’s life would vary according to her social status. Daughters in lower-class families might be expected to work in the family business, however, an upper-class girl like Lucia would probably not work outside the home. Instead, she would help her mother in supervising the household, learning how to one day run one of her own.

When a Roman matron went out, her stola mātrōnālis won her recognition, prestige, and respect. She was expected to have management skills and act as a responsible and respectable influence on the rest of the household. She often managed her own property outside the household as well. The students may be interested to learn that Varro’s first book on farming was dedicated to his wife and was intended to guide her in managing her own land. There were so many women with shipbuilding interests that the Emperor Claudius offered them special rewards if they co-operated in his new harbour and shipbuilding program. Examples of Pompeian women who seem to have been successful in business are given in Stage 2 on p. 30.

Houses in Pompeii

Insula 9 in Region I of Pompeii forms the basis for CSCP’s KS3 History course Amarantus and his Neighbourhood, materials from this might be of interest to show students how diverse neighbourhoods in Pompeii were. I.9 contains, for example, several grand houses, a painter’s workshop and a bar:

https://cambridgeamarantus.com/topics/topic-i/13/13-evidence

https://cambridgeamarantus.com/topics/topic-i/11/11-evidence

The ground plan of a Pompeian house on p. 13 of the textbook has been simplified to show the basic components of the domus urbāna. In reality, the house of Caecilius and Metella was more elaborate than the house depicted. In fact, his house and the one to the north had been renovated to become a single house. Once students have become familiar with the layout of a simple urban house, they may go on to study, interpret, or copy the plans of actual Pompeian houses.

You might wish to elaborate on the function of the atrium. Students can sometimes think of it as being like a “hallway”, but this doesn’t capture its importance. This was the formal or ceremonial centre of the house. Here the marriage couch was placed for the wedding night, here the patron received his clients, here the young man donned the toga virīlis, and here the body lay in state on a funeral couch. Not understanding this also risks minimising the role of Metella who is depicted in the atrium in her role as household manager. Students often think she is not doing anything or is a very passive figure, however she would in fact have been overseeing the enslaved people and keeping an eye on everything going on in her household. It may be helpful to point out to students that while the atrium in the model sentence image is rather empty – to aid in translation of the sentence - this would have been the bustling heart of the home through which everything and everyone passed. There would have been plenty more furniture and items like lamps and braziers, so houses might have felt a lot more cluttered than many today.

As mentioned in the textbook, there were many types of gardens in Pompeii including those used for production such as fruit orchards, vineyards, vegetable patches, and plant nurseries. Wilhelmina Jashemski cast the plant roots (in the same way the humans are cast) and then identified the plant species from the root cast. She also found many examples of carbonised food stuffs in the garden, for example pomegranates and beans. Many of the replanted gardens in Pompeii today are based on her findings, including the vineyards (as pictured on p. 17) which now produce wine. In fact, over time the focus on the atrium as the heart of the home changed and business became concentrated in the garden/peristylium of the house.

Illustrations

p. 8

The Bay of Naples including Pompeii and surrounding towns as well as Mount Vesuvius. The smaller map shows students where this region is in Italy in relation to Rome. This map is useful not only at the beginning of the course but also when towns such as Nuceria (Stage 8) and Herculaneum are mentioned in later Stages.

p. 9

Top right: The front of Caecilius and Metella’s house on the Via Vesuvio, which is the northern part of Stabiae Street (street plan p. 45). Like many prosperous houses on each side of the tall, imposing front door are shops which might have been leased out or managed by the owner’s enslaved people or freedmen. The adjoining house further up the street also belonged to Caecilius; part of the common wall had been renovated to permit access between the houses.

Middle left: One of the carbonised tablets from Caecilius’ archives

Middle right: A drawing of another one of Caecilius’ tablets showing the writing.

Bottom left: Strongbox, perhaps similar to the one in which Caecilius kept his tablets (Naples, Archaeological Museum). This box however is completely metal rather than the wooden (possibly with metal fixtures) chest that was found in the house of Caecilius.

Bottom right: The bronze head from Caecilius’ house (see notes on this at the beginning of this Stage).

p. 12

Top: Facade of the House of the Wooden Partition, Herculaneum, chosen in preference to one at Pompeii because of its more complete preservation. The doors open directly onto the sidewalk and the windows are small and high up as described in the text. The house is faced with painted stucco. The house further down the street, built out over the pavement (visible on the very left of the image) is timber-framed and contains a number of separate apartments.

Bottom: The main door of the House of the Faun in Pompeii. This image can be used to show students the view from the pavement through into the atrium with a clear view of the impluvium.

p. 13

Diagram showing the typical features of a Roman domus centred on an atrium. These houses are common in Pompeii, though with many individual variations; there are also smaller houses and apartments.

A larārium. Statuettes of the larēs (protective spirits of the family) and offerings of food, wine, and flowers would have been placed in this little shrine; its back wall might have been decorated with pictures of the household gods (lares and penates) and, often, protective snakes.

p. 14

Left: Atrium of Caecilius’ house, showing the impluvium surrounded by geometric patterned mosaic and the simple but still decorative floor. There is a little surviving painted plaster on the walls. We also see (on the left) the space called an āla (wing) that often opens off an atrium, the tablīnum, and garden behind.

Right: Atrium of the House of Paquius Proculus in Pompeii, located on the south side of the Via dell’Abbondanza. This house is relatively small but, as can be seen from the image, does contain some fine decoration. The floor of the atrium is made up of mosaic panels of animals framed with geometric borders and the walls are painted with panels.

p. 15

Caecilius’ tablinum. It had a rather plain mosaic floor and painted walls, with pictures of nymphs and satyrs on white rectangles against coloured panels designed to suggest hanging tapestries.

p. 16

Garden on the north-east side of the tablinum in the House of Caecilius. It is colonnaded on three sides and the columns consist of stuccoed brickwork. The walls still have some of their plasterwork, on which was found the piece of graffiti mentioned above on the merits of love. The garden has been planted to recreate the look of a Roman formal garden.

p. 17

This vineyard forms part of the “Villa of the Mysteries Project” which aimed to recreate the wines of ancient Pompeii using the same grape varieties and viticultural techniques. The winemakers worked with the Archaeological Superintendent of Pompeii to excavate the sites, study ancient wall paintings and test the DNA of the ancient vines. The site has now been producing wine for over a decade. Information about the wine and the project can be found here: https://www.taubfamilyselections.com/producers/mastroberardino/villa-dei-misteri-rosso-pompeiano

p. 18

Wall painting from the House of Venus in the Shell, Pompeii. The walls of gardens were often painted with trees, flowers, trellises, birds, and fountains to supplement the real garden and give the illusion that it was larger.

Further activities and resources

1. To provide a contrast to house of Caecilius and Metella, students could investigate life in the insulae/apartments in Pompeii. Useful resources include:

- CSCP’s Amarantus and his Neighbourhood project: https://cambridgeamarantus.com/

- Magister Craft’s (spoken Latin!) video created using Minecraft: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d22sGxMIzGk

- Mary Beard's Meet the Romans Episode 1

2. Students may research other examples of houses in Pompeii using resources such as:

- http://pompeiisites.org/en/pompeii-map/

- https://pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/

- https://sites.google.com/site/ad79eruption/pompeii

- Some of the many excellent reconstructions found on YouTube such as this one of The House of Caecilius: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ETd7pszxhnc

This might lend itself to a creative task such as:

- an estate agent’s advertisement for a Pompeian house

- a piece of creative writing imagining who may have lived and worked in the house they have researched

Vocabulary checklist (p.18)

- Students will already be familiar with all or most of these words since they will have occurred several times in the material. It is helpful to ask them to recall the context in which they met a word because the association will help to fix it in their minds.

- Discussion of derivations is valuable for extending students’ vocabulary in English and other modern languages, and will also reinforce their grasp of Latin.

Suggested further reading

- Allison, P. M. Pompeian Households: An Analysis of the Material Culture (Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2004)

- Beard, M. The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found (Harvard University Press, 2008)

- Berry, J. The Complete Pompeii (Thames & Hudson, 2007)

- Cooley, A.E. & Cooley, M.G.L. Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (Routledge, 2014)

- MacLachlan, B. Women in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook (Bloomsbury 2013)

- Wallace-Hadrill, A. Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum (Princeton University Press, 1994)