Stage summary

| Storyline |

A friend comes to dinner, and everything must be perfect. |

|---|---|

| Main language features |

Nominative and accusative singular |

| Sentences patterns |

nominative + accusative + verb |

| Cultural context |

Daily life for Caecilius, Metella and Grumio: clothing; working women; food. |

| Enquiry question |

How did Caecilius’, Metella’s and Grumio’s daily activities reflect and reinforce their social status? |

Sequence and approach

You may wish to introduce the cultural material in sections where it best relates to the stories; Daily Life with mercātor and Dinner Parties with in trīclīniō.

Illustration: opening page (p. 19)

Reconstructed bedroom from a villa at Boscoreale, near Pompeii, owned by Publius Fannius Synistor, a very wealthy man. The high elegant bed (or it may in fact be a dining couch) with its pillow bolsters requires an equally elegant stepping stool. The walls are decorated with architectural panels drawn from theater scenes of comedy, tragedy, and satyr plays (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Model Sentences (pp.20-23)

New language feature

The accusative is introduced not in isolation but in the context of a common sentence pattern: nom + acc + v.

New vocabulary

amīcus, salūtat, spectat, parātus, gustat, anxius, laudat, vocat.

First reading

Introduce the situation briefly, e.g. “A friend (amīcus) is visiting Caecilius.” Then take the first pair of sentences as follows:

If students ask, “Isn’t his name Caecilius?”, congratulate them for noticing the change and confirm that they should continue to use the form Caecilius when referring to him. Do not enter into explanations yet, instead encourage students to look for patterns as you read the following sentences.

Sentence 1. Read in Latin, then ask who is in the picture and where he is.

Sentence 2. Read in Latin, then explore the situation, e.g. “Who is in the picture with Caecilius? What is he doing?”

Read the Latin sentence again and ask for the meaning. Encourage a variety of meanings for salūtat, e.g. says hello, greets. The main aim is to establish the grammatical relationship between amīcus and Caecilium.

Repeat the process with each pair of sentences as far as 10. Most students are quick to understand the new sentence pattern.

Run through sentences 1–10 quickly again, with pairs of students for each pair of sentences. Students should read their sentences aloud and translate them.

Be flexible. If you feel that students already understand the point, then move on; there is no need to dwell on this pattern recognition once students have grasped it.

Follow the same process with the picture story about Metella in sentences 11–20. If there are questions about the new endings, ask the students if they can suggest what the new endings indicate. Rather than introducing the terminology of “nominative” and “accusative” at this stage consider focusing on the students looking for patterns and suggesting theories about those patterns. They might test their theories in the reading that follows.

Consolidation

Reuse the pairs of sentences for quick oral drill in the next lesson or two, to reinforce the natural English word order for translating the second sentence.

These sentences are also useful for exploring the relative positions and roles of enslaved people and women in the household. You might ask students why Metella is keeping such a close eye on Grumio (Metella as domina takes responsibility for checking on the work of the enslaved members of the household and ensuring the food served to their guests is of a good standard) and why Grumio is anxious to hear Metella’s verdict (model sentence 17) (she has great power over him; if she is displeased he might be punished).

About the language (p. 25)

New language feature

The difference in function and form between the nominative and accusative. Note that explicit identification of the different declensions is postponed until Stage 3. This is to allow for students to focus on the idea of nouns having cases (a very unfamiliar one to most if not all of them) before being given unnecessary (at this stage) extra information.

Discussion

Start by putting one pair of model sentences on the board (e.g. Caecilius est in ātriō. amīcus Caecilium salūtat.)

Q: Caecilius appears in both sentences, but there is a difference between the ways in which he appears in the Latin. Point out the difference.

A: In one he is Caecilius, in the other Caecilium.

Q: Good. Both Latin words mean “Caecilius,” but they have different forms. Why might this be?

Guide the students to realise that Caecilius is used when he does the action and Caecilium when he receives the action. Then display other sentences with accusatives (including endings in -am, -um, -em) and invite comment. As students grasp the grammatical pattern, introduce them to the names (nominative and accusative) for the two different forms of the noun. Student observations will usually include:

- The nominative (subject) shows someone who does something.

- The accusative (object) shows someone who has something done to him or her.

- The accusative ends in -m.

- The Latin accusative follows the nominative, but the English translation has the corresponding word at the end.

Study About the language. Add further examples, if necessary, always in complete sentences, using familiar words and retaining the nominative + accusative + verb word order. Concentrate on using the terms “nominative” and “accusative” and explaining their characteristic endings, rather than introducing additional terms such as “subject” and “object.” If students themselves use these terms, confirm that they are correct, but continue to use the case names.

Consolidation

Go back to the stories on p. 24 and ask students to pick out nominatives and accusatives. For instance, taking in triclīniō:

What case is coquum in line 6? How do you know?

In Poppaea coquum spectat (line 13), which word is nominative? How can you tell?

Sometimes ask for the translation of the sentence under discussion, to remind students of the grammatical relationship shown by the case names.

Illustration p.25

Peacock wall painting (Naples, Archaeological Museum).

Practising the language: in culīnā (p. 26)

The Practising the language stories have been designed to be used flexibly by teachers and learners to address individual circumstances and needs, and to give students a variety of opportunities to reflect on their learning.

Students could be asked to demonstrate their understanding of this and other Practising the language stories in many ways, using the questions as prompts to check that they have addressed core aspects of the narrative. Activities could include producing detailed summaries, creating cartoon strips or freezeframes, or rewriting the story from a different perspective (e.g. the hungry Corvus).

Grumio finds an uninvited guest in the kitchen.

Throughout this story there are pairs of sentences which show the nominative and accusative of the same noun in quick succession. These can be used to check comprehension of case form and function. For example:

Corvus Clēmentem videt. Clēmēns Corvum salūtat. (lines 2-3)

Corvus cibum gustat. cibus est optimus. (line 6)

Grumiō amīcum videt. amicus cibum cōnsūmit! (lines 7-8)

1. Explore the story

If you wish to assign marks to these questions, here is a 10-mark scheme:

a) What two things are we told about the friend? [2]

He is visiting Grumio [1] and his name is Corvus [1]

b) What happens after Corvus sees Clemens? [1]

He greets Clemens [1]

c) Which two of the following statements are true? [2]

C [1] and D [1]

d) What two things does Grumio do? [2]

Grumio enters the kitchen [1] and sees his friend [1]

e) Why is the cook angry? [2]

His friend is eating the food [2]

f) What does the cook say as he rebukes his friend? [1]

‘Pest! Scoundrel!’ [1]

2. Explore the language

This section asks students to explain the nominative and accusative in their own words. Responses may explain that the forms are being used differently in each sentence: one is doing the action, whilst the other is receiving it. Students may use the terms nominative and accusative, or subject and object.

The call-out box here links students back to Stage 2 About the language where they will find the prompts and the English vocabulary to access the question and formulate their response. It may be helpful to address this question in a collaborative setting such as peer discussion groups to enable students to work through their ideas before formulating conclusions.

3. Explore further

Discussion could include:

- attitudes to eating: Caecilius and Barbillus view eating as a social experience rather than a necessity. Caecilius and Barbillus use dining to cement relationships and to impress others;

- the experience of dining: Caecilius and Barbillus recline at ease, whilst the enslaved characters hurry to eat when they can;

- access to food: Caecilius and Barbillus eat and drink until they are full, whereas the enslaved characters are seen to be frequently hungry.

Further discussion

Narrative moments which could be discussed further include:

- amīcus vīllam intrat. Clēmēns est in ātriō (lines 1-2): Corvus walks in through the open front door. How does Caecilius make sure that unwelcome guests cannot come in? Do you think that Corvus is free or enslaved? Why do you think that he might be allowed into the house? How do you think that Grumio and Corvus know each other?

- Grumiō nōn est in culīnā (line 5): there is a big dinner party this evening, but Grumio seems to be busy elsewhere. What other tasks might he have been given as well as the cooking?

- Corvus cibum gustat (line 6): why do you think that Corvus does this?

- coquus est īrātus (line 8): why do you think that Grumio is angry? What might happen to Grumio if the food is not perfect?

Reviewing the language

If students are ready to consolidate their learning, exercises for this Stage can be found on page 223.

Latin sentences 2: sentences of the type nominative + prepositional phrase + verb. Students select an option from the box to complete the sentence so that it makes sense. Students should be encouraged to consider the sentences alongside the stories they have been reading: some combinations are more likely than others. Students should then translate their sentences. If students need to revisit Latin sentences 1 before completing this section, these exercises can be found on page 222.

Nominatives and accusatives 1: sentences of the type nominative + accusative + verb. Students select the correct verb to complete a sentence which makes sense, choosing one of the two options given in brackets. Students should then translate their sentences.

Cultural context material (pp. 27–33)

A description of daily life for the different members of the household including meals, dress, and work. Dinner parties are treated in their own section.

Enquiry

Further reading on teaching similarity and difference can be found on the Historical Association’s webpage “What’s the wisdom on… Similarity and Difference” here: https://www.history.org.uk/secondary/categories/653/resource/9917/whats-the-wisdom-on-similarity-and-difference

How did Caecilius’, Metella’s and Grumio’s daily activities reflect and reinforce their social status?

This Enquiry targets the second order concept of similarity and difference. Not only is this concept important for good historical understanding, it also enables better reading of the stories, and (later) Latin literature, by highlighting the numerous experiences of people in the past. This question also offers opportunities to investigate the power dynamics at play in the Roman world. Students should come away from this section with a better grasp of the relative statuses of men, women, and enslaved people.

When setting the task for this Enquiry, consider how it might be integrated into comprehension of the stories; all the stories in this Stage lend themselves to discussion of daily lives and status. Could material from the stories be used to form a more creative response to the Enquiry? Possible tasks:

- Diary entries. Have students write a diary or schedule for each of the three characters. They might consider how to reflect the characters’ attitudes towards themselves and others to explore their relative statuses; this is a good opportunity to develop students’ creative writing skills.

- Cartoon strips. A set of perhaps four drawings to show what each character is doing at each point in the day. This might be annotated with comments about status or (if the students are particularly creative) this might be portrayed through the cartoon itself.

- Compare and contrast table. Create a table with three columns, one for each character, with rows labelled ‘clothing’, ‘food’, ‘work’ etc. You may wish to add in some rows which require students to look back to Stage 1 and review information from there, for example ‘names’. Alternatively, you could create one that tracks the daily schedule of each character. If integrating the stories, perhaps create a more complex worksheet which includes space for what the stories tell us about the characters and their positions in society.

Thinking points

Not all Thinking points need to be studied. Select those most relevant to your and your class’s needs and interests.

1. Think about the stories and cultural background material you have read and the pictures you have seen. What do you already know about daily life in Caecilius’ household?

This opening question asks students to recall past information before considering the new. Stage 1 alone contains a great deal of information from which students might infer things about daily life. For example, they may mention things they have seen members of the household doing in illustrations and stories, how they dress, and information from the cultural background about how Caecilius made his money.

2. Look at the statue of a Roman wearing a toga and think about Caecilius’ description of getting dressed. What do you think it would be like to wear one for a day? Why do you think male Roman citizens went to the trouble of wearing them?

This is of course a very subjective question, but it is likely that many students will be grateful for their far lighter and less complicated modern clothes! The reason for such trouble was the status symbol of the toga, a sign that one was free and probably wealthy. You may wish to extend this discussion to clothing from other cultures or time periods – clothing which might not be the easiest thing to wear, but has important social connotations.

3. Why do you think Roman women a) wore the palla over their heads and b) used powder to whiten their skin?

As is the case in many cultures today, covering the head was a sign of modesty and respect. Roman women therefore covered their head and hair in public if they wanted to convey a sense of respectability. This might be an interesting point to talk about the ways in which different cultures respond to women’s bodies; what this tells us about Roman expectations of women; how this all fits in with the other things they have learnt about the status of Roman women (for example naming and marriage conventions mentioned in Stage 1).

The fashion was also for whitened skin (reflected in the Course illustrations in which women like Metella are markedly paler than others) probably because it suggested the individual was wealthy and did not have to do hard labour outside in the hot sun. You may draw a contrast with 20th and 21st century, western fashions for suntanned skin (and the popularity of fake tan), due to the implication that tanned people could afford expensive holidays. Conversely, many women in Korea lighten their skin due to their cultural context.

It is important to challenge any assumption that lightening the skin was racially motivated. This is an opportunity to stress that Roman thinking about skin colour is completely different to modern thinking; the Romans did not have a concept of white or Black ‘races’ the way we do today (although they could be deeply xenophobic, including about the appearances of people from other cultures). Whiteness (as we would use the term today) did not denote Romanness; Barbillus in our stories has black skin but this would have had no impact on whether or not people saw him as Roman.

4. What do you think was the purpose of the salutatio? How did both the clients and the patron benefit from this relationship? Do you think they benefited equally?

The salutatio was all about reinforcing the status of the patrons and clients, a daily reminder of who held the power. Clients got protection, support, potentially wealth and better standing in society. Patrons got support for their endeavours, favours, and the status that comes with being patron to many and/or impressive clients. Students may debate who benefited more in real terms as long as they recognise the power imbalance between the parties.

5. Based on the descriptions of Caecilius and Metella in Stages 1 and 2, which character’s daily life is more appealing to you? Why?

This discussion should be carefully framed to take account of the different statuses of these characters, as well as what they do with their day. Student responses will vary considerably based on their own preferences and experiences, but the discussion should be carefully framed to make sure students understand that Metella may not work outside of the house, though her contribution and responsibilities would still have been considerable. Students can sometimes simplify the situation to “Metella doesn’t do any work” which is an inaccurate presentation of her life.

6. How typical of Roman women do you think the character of Metella is?

The answer to this question should be ‘it depends on the type of women’. Metella is a fairly typical upper class, wealthy woman. She is not, however, typical of the vast majority of women in the Roman world who would have been far less affluent and often working to contribute financially to their households.

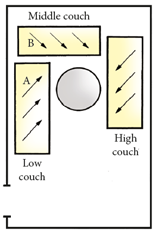

7. Look at the diagram showing the arrangement of the couches. Where would Caecilius have been seated? What position might a good friend be given? If she attended, where might Metella be?

As the host, Caecilus would be seated in Position A on the low couch. A good friend with good social standing, or someone Caecilius wanted to impress, might go in Position B. You can see from the arrows how this position is closest to the host and if they are all lying on their left sides, Position B is facing towards Position A, allowing for easy conversation. If there was someone more important present, then a friend might join Caecilius on the low couch. It is likely that this would be where Metella would recline as well.

8. Why might some hosts have given different food to different guests?

Answers may include because they can’t afford for everyone to have the very best food or because they want to emphasise the social status of their guests, reminding those of lower status of ‘their place’.

Further information

The times of meals and work during the Roman day were earlier than ours. This information could provoke discussion of the effect of the Mediterranean climate on daily life then and now, and of the absence of strong artificial light in the ancient world. The use of sundials (see image of Anaximander on p. 161) might raise questions about how accurately and how often the Romans needed to tell the time. The Romans divided the daylight time into twelve hours. If one is using a sundial to keep track, then an hour (i.e. one-twelfth of the period of daylight) could be forty-five minutes in midwinter, seventy-five in midsummer.

You might want to prepare by consulting McLeish or the British Museum blog for Roman recipes (both can be found in the select bibliography at the end of this Stage guide).

Informal family meals including iēntāculum (breakfast) and prandium (lunch) were eaten standing or sitting; reclining on one’s elbow was a formality generally practised at the cēna (dinner), especially when guests were present. As mentioned in the textbook, not everyone would have attended formal dinners and only wealthy people had ground floor homes with kitchens and triclinia. A poorer household may well have had had no kitchen at all. This is naturally linked to the amount of thermopolia and bakeries found in Pompeii.

It is important to ensure that students realise that formal dinner parties in lavish dining rooms were not everyday occurrences even for the rich. The average Roman would probably have never attended one at all. It is also important to stress that all the cooking, serving, and caring for guests would have been done by enslaved people. These people can be identified in frescoes (for example p. 33) by their size; they are shown considerably smaller than the others present. You may wish to ask students to comment on this as part of the discussion about the statuses of enslaved people and those who held them in slavery.

Reclining to eat, while possibly an odd notion for us, was not unique to the Romans. Wealthy ancient Greek men also reclined for formal (men only) dinner parties in a similar manner. The practice may have been imported from cultures from further east. It was a popular practice in the Roman world from the second century BC, although we are not sure how widespread it was before this. Reclining at dinner does seem to have been common for the neighbouring Etruscans and is depicted in several sources including on pots and in wall paintings dating to the 6th and 7th centuries BC. It is likely that the Roman aristocracy adopted the practice around this time as well, and that patrician families continued the practice into the subsequent centuries. Over time, wealthy households with adequate space increased the number of couches and hosted bigger dinner parties. Eventually, the a semi-circular stibadium replaced the three couches. Literary references to reclining at dinner decreased in the 3rd century A.D., but dining rooms including couches for reclining continue to be a feature of wealthy households into the 6th century.

As mentioned above, the Greeks had a strict ‘no (respectable) women’ policy at their dinner parties. The only women who seem to have been in attendance were there to serve the food or provide entertainment. Some were sex workers. Respectable women sat upright on the rare occasion that they attended a formal meal, such as at a wedding. In contrast, the Etruscans often represented female diners in their artworks, and it seems that they were common guests at family, civic and religious banquets. In the Roman world, we can clearly see women reclining alongside men in frescoes and other sources as standard by the time of the Emperor Augustus. The 1st century author Valerius Maximus (Of Ancient Institutions 2.1.2), however, stated that in previous times, while women may have dined sitting with men, only the men reclined.

Illustrations

p. 27

Roman statue of Augustus wearing a toga (Louvre Museum).

p. 28

Left: Statue of Livia Drusilla wife of Emperor Augustus from 14-19 AD. From Paestum (Italy) (National Archaeological Museum, Madrid, Spain)

Middle: 1st century BC marble bust of Julia, daughter of Emperor Augustus with a typical hairstyle from the Flavian period.

Right: Examples of Roman jewellery found in Pompeii, all now in the Archaeological Museum, Naples. Clockwise from top left: gold earring in the shape of a bulla; gold bracelet in the shape of a snake; pair of gold pins decorated with pearls.

p. 29

The doorway of the House of Menander in Pompeii showing the remains of stone benches on either side.

p. 30

Photograph of fresco of a female shopkeeper from the façade of the House of the Fullers of M. Vecilius Verecundus. The shopkeeper stands behind a wooden counter while a customer sits on a bench on the right chatting and gesturing.

p. 32

Top: mosaic detail with fish from House of the Faun, Pompeii. Pompeii had a lively fish trade and produced and exported fish sauces (garum).

Middle: wall painting of a larder (Naples, Archaeological Museum).

Bottom: fresco detail of a bowl of fruit from the villa of the Poppaei family at Oplontis. Note the artist’s skill in showing transparent glass.

p. 33

Fresco from the House of the Triclinium depicting a dinner party. The smaller figures are enslaved people and in the right-hand lower corner is a man vomiting.

p. 34

Bronze vessels from the kitchen of the House of the Vettii in Pompeii.

Further activities and resources

1. Imagine you are a cliēns of Caecilius and write an account of your morning visit to Caecilius’ house. Include a description of your surroundings and the conversations that occur.

2. Design an invitation to a Roman dinner party, with the menu and a description of the entertainments.

3. Sample some Roman dishes or simulate a Roman dinner party. Stuffed dates, ham and figs, and pork and apricots are easy. Pickled eggs, alcohol-free wine, olives, grapes, and almonds can be bought from any supermarket. Extra resources on Roman dining include:

- The blog “Cook a Classical Feast” from the British Museum (2020) available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/cook-classical-feast-nine-recipes-ancient-greece-and-rome

- Video of Last Supper in Pompeii curator Dr Paul Roberts speaking about Roman dining: https://www.ashmolean.org/article/dining-in-pompeii

4. Look at the examples of wall paintings in the first four Stages. Then design a simple wall panel and colour appropriately.

5. Make an illustrated diary of a day in the life of Caecilius, Metella and Grumio. Set them side by side so that they can be compared.

Suggested further reading

- Aldrete, G. S. Daily Life in the Roman City: Rome, Pompeii, and Ostia (Greenwood Press, 2004)

- Allison, P. M. Pompeian Households: An Analysis of the Material Culture (Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2004)

- McElduff, S. UnRoman Romans (online) available at https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/unromantest/

- McLeish, K. Food and Drink (Greek & Roman Topics) (Collins, 1978)

- Rawson, B., ed. A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds (Blackwell, 2010)

- Rawson, B. & Weaver, P. The Roman Family in Italy: Status, Sentiment, Space (Oxford Clarendon Press, 1997)

- Roberts, P. Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum (British Museum Press, 2013)

- Roberts, P. Last Supper in Pompeii (Ashmolean Museum Publications, 2019)

- Sebesta, J. L. and Bonfante, L. The World of Roman Costume (University of Wisconsin Press, 1994)

- Stone, B. The painful art of being a Roman woman (blog) available at https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/lucius-romans/2018/03/15/the-painful-art-of-being-a-roman-woman/